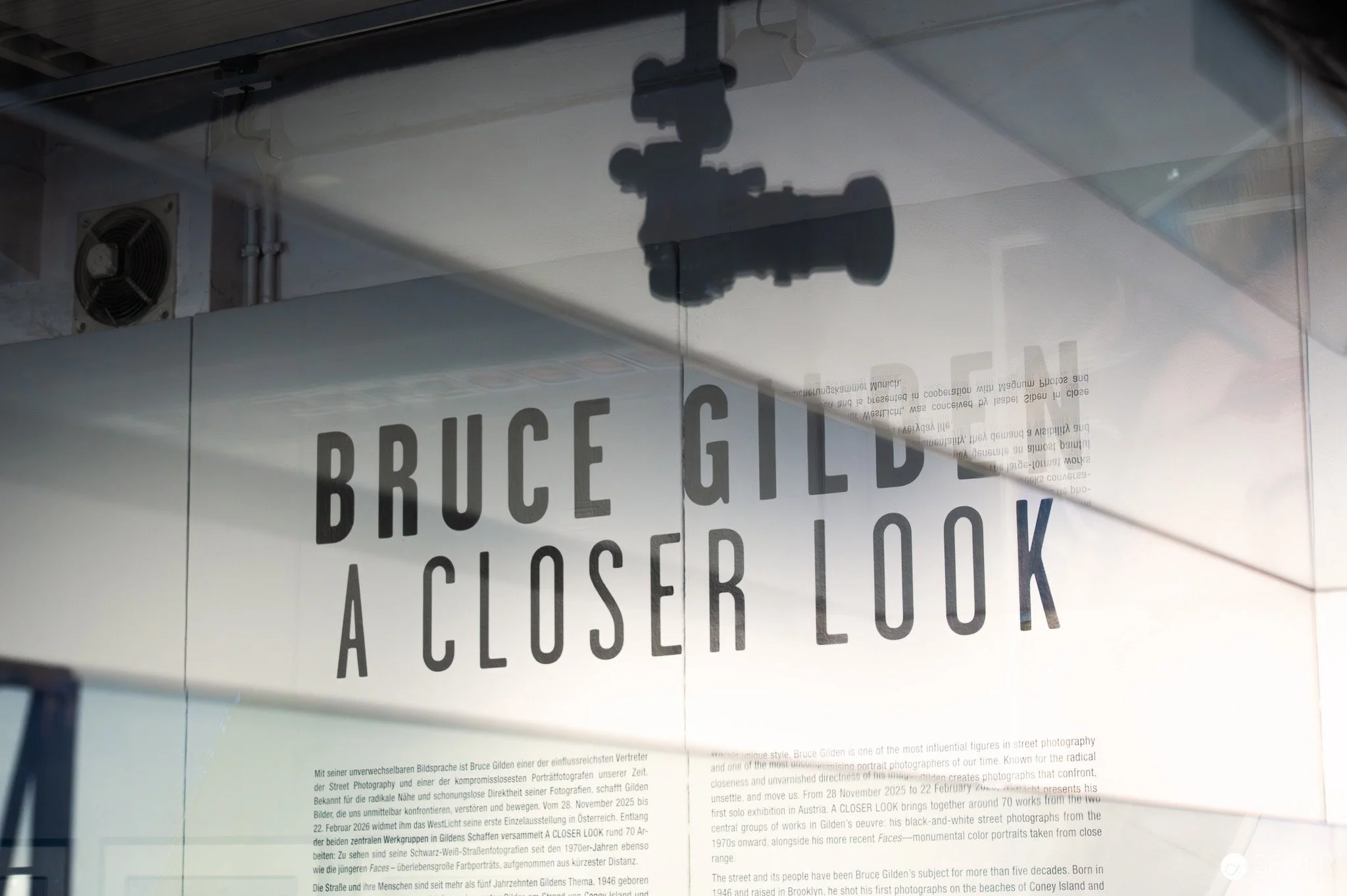

If You're Not Close Enough, You're Not Bruce Gilden (Exhibition at Westlicht)

Bruce Gilden doesn't ask permission. At 79, the legendary Magnum photographer has spent decades getting closer to his subjects than most would dare - armed with a flash, sharp instincts, and a personality forged on the streets of Brooklyn. During a recent gallery talk, Gilden walked visitors through his extensive body of work spanning Coney Island, Haiti, Japan, and the gritty corners of cities worldwide. His guiding principle? Robert Capa's famous advice: "If it's not good enough, you're not close enough."

„I’m known for taking pictures very close, and the older I get, the closer I get.“

From Coney Island to the World

Gilden's journey began at Coney Island in the early 1980s, where he developed his signature style - candid, confrontational, and unflinching. He recalls photographing beachgoers while wearing army boots and a jacket in 90-degree heat. "You could see me," he laughs. His first trip to Haiti in 1984 sparked a 22-trip love affair with the country. "Where have I been my whole life?" he remembers thinking upon arrival.

Photographing Yakuza and Bikers

In Japan, Gilden embedded himself with Yakuza members. In America, he spent years with outlaw bikers. How does he gain access? "If you want something, you'll figure out a way," he says. His gangster father taught him how to navigate tough circles. You need to be street-wise he says, which means you need to know exactly when you can take a shot or when to better hide your camera.

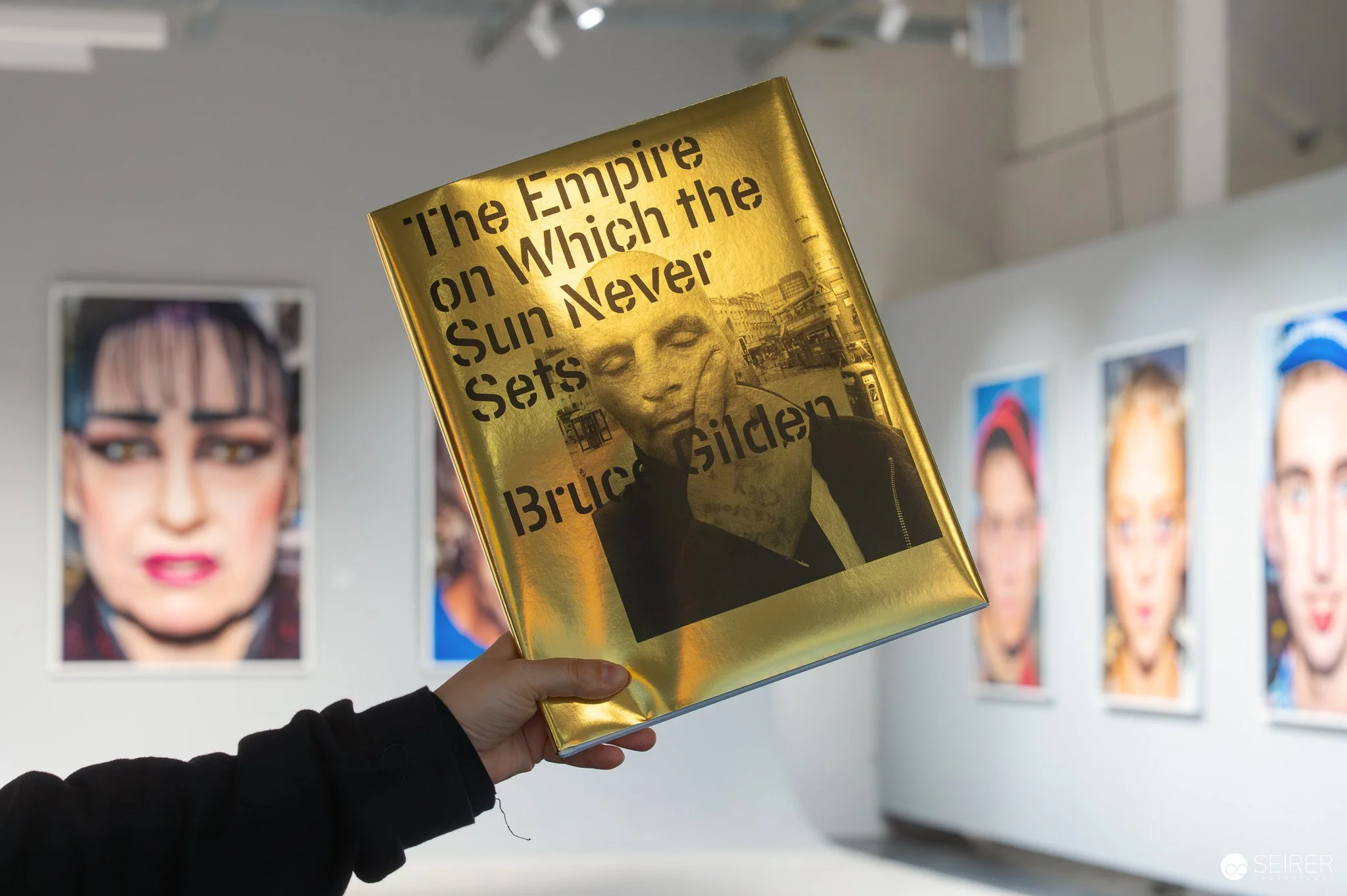

Bruce Gilden at Westlicht, 2025

On Exploitation

Gilden's large-format portrait series marks a dramatic shift from his kinetic street work. Inspired by early 20th-century police mugshots - which he considers some of the best portrait photography ever made - he waited 25 years before finally pursuing the project. Shot in color with a Leica S, these extreme close-ups reveal every pore, scar, and wrinkle with unflinching clarity. Getting close again, but quite differently this time.

Bruce Gilden at Westlicht, 2025

Where Richard Avedon's "In the American West" maintained a certain noble distance from his working-class subjects, and Diane Arbus sought the strange within the ordinary, Gilden pushes further into discomfort. He doesn't flatter. He doesn't soften. The result is confrontational intimacy - faces of addicts, sex workers, and outsiders rendered with the same technical precision fashion photographers reserve for supermodels. It's this refusal to distinguish between "worthy" and "unworthy" subjects that makes the work radical. At 79, with less stamina for chasing shots on the street, Gilden found a way to bring his intensity into a single frame: one person, nowhere to hide. And he looks out for faces that are interesting him - when visiting an event with tens of thousands of people he might take photographs of only one person.

„When people look at my photographs, I don’t want to tell them what’s in the picture. I want them to look at it and make up their own story.“

When accused of exploiting marginalized subjects in this series, Gilden pushes back hard. His intent isn't to use people to boost his fame - it's to make us see them. These are human beings who exist in our society, whether we acknowledge them or not. By photographing them, Gilden holds up a mirror, asking viewers to reflect on their own lives and the world we've collectively built. "I look at them as human beings," he insists. For him, the real dismissal is refusing to photograph society's edges - pretending they don't exist.

Agree with his methods or not, Gilden's work endures because it refuses to look away. And forces you to look at them.

Other blogposts that are interesting: